This morning it finally occured to me: I am a confessional poet.

At my favourite coffee shop—Bean Scene—I picked up my pen. Two hundred and something lines about ‘confidence’. Due by the 28th.

I’ve been working on this for a few weeks. Getting lines down. Capturing moments. My last crack resulted in some cohesion but no cigar. I had been aiming to write wisdom poetry but found it was pushing back. I can do wisdom in the form of Rumi—short, pithy, to the point, maybe twenty lines if necessary—but exegetical wisdom in poetic form…

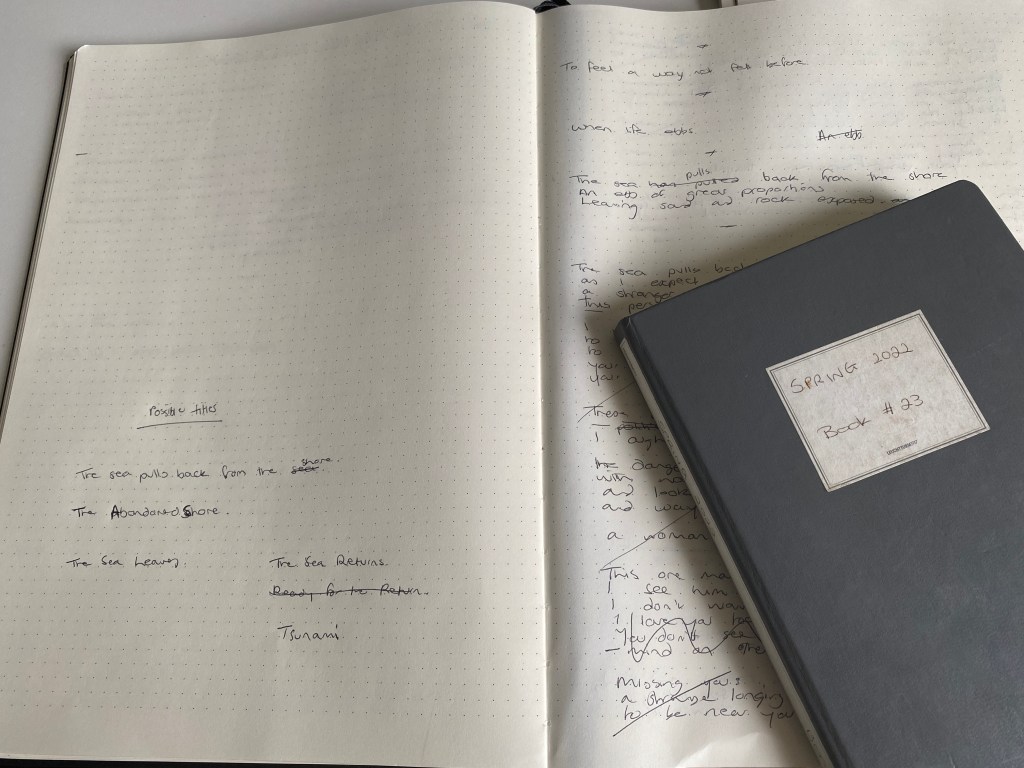

I put the wisdom poetry aside and began with the word ‘ebb’.

The tap turned on. A moment of ‘ebb’ flowed into thoughts about love, childhood, and into a representation of healing. One hundred and something lines later, I captured the movement required for me to feel ‘confident’.

So it seems odd, even to me, that today the label ‘confessional’ has landed with me. I’ve only spent the last five years up to my eye-balls in the genre.

To write confessional poetry is not about listing sins or trying to shock the writer by being outrageous, although some folks write as if it is. I best not get sidetracked with my opinions about poorly written but shocking memoirs.

Confessional poetry is a complex genre that involves the appearance that the poet is pouring out their deepest woes. And in some ways, they are. Technically, however, what is happening is the employment of a poet persona. This persona explores something that might be personal but it is unlikely that the thing being explored will remain unresolved by the time the writing process is complete. Agency always remains with the poet.

The 1950s and 60s saw a group of poets emerge who were considered “Confessional”—capital C—poets. They included the likes of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Robert Lowell. Connected socially through Lowell, a university lecturer teaching poetry, they and others such as Robert Snodgrass and John Berryman, didn’t consider themselves “confessional”. Some were even offended by the label (given to them by critic M. L. Rosenthal).

What drew the label was the nature of their writing. They wrote about things that seem antiquated these days—what it means to be a woman, to have a period, childbirth, marriage, sex. These poets explored the state of their inner lives, their private lives, seeking meaning through writing.

Modern confessionals are more complex. They have to be. Poetry has progressed. The idea of what is private has changed. Time has been spent considering what is means to be confessional.

These are also different days. There is no subject too delicate for the internet and so to label a poet confessional because they explore private things simply isn’t enough to employ the full meaning of the label. There has to be more.

Louise Glück, an American confessional poet and prolific writer, adds imagination to her confessional style. She changes gender or takes on a different point-of-view persona, for example. Her writing contains the essence of the confessional edge: it exists in the vulnerable. It is easy to mistake things as her personal opinion, rather than the outworking of an art form that is exploring an idea through not only content but form. That is not to say that she is misrepresenting herself. The poet persona is a subtle concept.

Australian confessional poet, Maria Takolander inhabits in a similar space. Her poetry contains raw edges and exists as embedded emotion in the physical. These poems are the exploration of life being lived, fueled by the energy that is life itself. Takolander writes other things—most poets do. It is her confessional work, both poetic and academic, that captures my interest.

Likewise, I am also interested to read Australian poet, David McCooey. I am currently waiting on the arrival of his latest collection The Book of Falling to see how he dips into the confessional, if he does at all. Married to Takolanda, surely there must be something with a confessional edge.

I don’t mean to pigeonhole McCooey before I have read the collection, he writes broadly, I have, however, noticed an engaging confessional edge when capturing relational moments. My curiosity abounds. Where on the confessional continuum will this collection sit?

If you have ever written poetry, it is likely that you, too, have dipped into the confessional. Confessional poetry calls to struggle, suffering, and celebration.

Often when our hearts are low, we are comforted by placing that burden on a page. For a little while we can consider our lives from the outside. Poetry offers its form as a gift to formless pain, draws attention to the things that matter, and helps us move forward by holding, but not domineering, our pain.

Beginning with the word ‘ebb’ this morning led me to see that there are times when suffering takes the form of an empty shore before a tsunami. That moment when the ocean retreats, we now understand, is not the worst of what will happen.

Knowing that allows us to face it, prepare, and be brave.

Thanks for sharing! Interesting concept to incorporate.

LikeLike

I enjoy reading and writing confessional poetry! I believe that it’s healing.

LikeLiked by 1 person